Dr. Abby Gondek, Morgenthau Scholar-in-Residence, FDR Library, Hyde Park, NY

PhD Global and Socio-cultural Studies, Florida International University

MA African and African Diaspora Studies, FIU

MA Women’s Studies, SDSU

For the roundtable: The politics of knowledge in jewish women’s activism @ NWSA 2019

November 14, 2019 in San Francisco, CA

Abstract

Fatima Meer (1928-2010), a feminist sociologist of Indian Muslim (on her paternal side) and Jewish descent (on her maternal grandfather’s side) in South Africa, collaborated with Hilda Kuper (1911-1992), a Jewish anthropologist (born in Rhodesia), producing “The Indian Elites in Natal, South Africa” (1956). Meer conducted fieldwork and influenced Kuper’s Indian People in Natal (1960) as well as Kuper’s play The Decision (1957). One of the themes in Meer’s work was black and Indian women’s experiences of racism and sexism and the use of suicide as a mode of resistance within apartheid South Africa (1976). This presentation explores how Kuper and Meer influenced each other’s writings and anti-apartheid activism.

Organization

I begin with an explanation of Hilda Kuper & Fatima Meer and then move into their collaboration, focusing on the publications they wrote together or that were thematically connected. In part 3, I detail the timeline of their relationship. In the last section, I describe Hilda’s play The Decision, influenced by her research with Fatima Meer and discuss their overlapping themes such as suicide and different types of elites within the Indian community in South Africa.

Part 1: Intro to Hilda Kuper & Fatima Meer

Hilda Kuper was born in 1911 in Bulawayo, Rhodesia, grew up in Johannesburg, South Africa and received her anthropological training with Winifred Hoernlé at the University of Witwatersrand and Bronislaw Malinowski at the London School of Economics. Kuper’s first fieldwork involved studying the impact of liquor laws on black women in Johannesburg. Later her research sites expanded to Swaziland and Indian communities in Durban, Natal, South Africa, where she formed a life-long friendship and research partnership with sociologist, Fatima Meer, who was of South African, Indian, Muslim and Jewish descent. Their collaboration will be the focus of this presentation.

Through Hilda’s marriage to Leo Kuper she became involved in non-violent apartheid protests as one of the founders of the Liberal Party and was forced to leave South Africa; she eventually became a Professor of Anthropology at UCLA.

In her theorizing about black women, Hilda took a “Swazi point of view,” arguing that Westernization weakened women’s position. She portrayed Swazi women and Indian South African women as the victims of colonization as well as patriarchal indigenous systems.

Hilda’s initial interests in law, acting, languages and history, morphed into her career as a legal and political anthropologist, novelist and playwright. Durkheim and French sociology were also highly influential, as both Hilda and her research collaborator, Fatima Meer, wrote about suicide and women of color in Southern Africa.

Hilda’s graduate student at UCLA, David Kuby, said the following of her Jewish identity:

“Jewish, British and African are quite a combination of values not easily put into one neat box and there was a comfortable, very human dimension of Hilda that was humble and nonjudgmental that made one feel very accepted in our imperfections despite Hilda’s high standards for scholarship and social justice work.”

-David Kuby, December 29, 2016, e-mail correspondence

The information in this section comes from a brief bio I wrote of Hilda, based on my dissertation. You can find the full bio I wrote here on my academia.edu page and the excerpt from it was published at Bustle.com.

“Meer’s Gujrati grandfather, Ismail, had arrived in South Africa as a trader from Surat on the east coast of India in the 1880s. Her father, Moosa Meer, was the editor of Indian Views, a weekly in Urdu and English. Her mother, Ameena, was a white woman [whose father was Jewish] originally called Rachel. The Meer household was a mixture of Muslim Gujarati traditions and liberal political activism; Fatima combined the two.”

Wajid, Arjumand. 2010. “Fatima Meer: Academic and Activist.” The Hindu, March 30, 2010.

“At a time when most Indian girls were helping their mothers in the kitchen making samosas, this young woman was leading protest marches and challenging the most oppressive system in the world.”

Winnie Mandela

From the Wajid obituary of Fatima Meer, March 30, 2010.

An article about Fatima’s artwork that was created while she was in the Women’s Gaol in Johannesburg has just come out this October in the New Yorker magazine. I visited the Gaol in March 2017, while in Johannesburg for my dissertation research. You can also learn about Fatima’s art work during her imprisonment here.

“…in 1976, [Fatima Meer] was held for six months, without trial, under the apartheid government’s Terrorism Act. Her crime was an attempt to organize a mass rally with the activist Steve Biko, after police shot at and killed student protesters in the township of Soweto.”

Anakwa Dwamena, October 23, 2019, The New Yorker

Part 2: Writing collaboration

Hilda collaborated with Fatima Meer on a project about Indian South Africans in Durban, Natal (Kuper and Meer 1956).

This network visualization displays the publications written by Hilda Kuper and Fatima Meer. “Indian Elites in Natal” (1956), co-authored by Kuper and Meer, shared a thematic focus on Indian South Africans and protest with Hilda’s book Indian People in Natal (1960), for which Fatima Meer acted as a research assistant. “Indian Elites” also shared an emphasis on Indian ethnic groups, such as Tamil and Hindustani, with Hilda’s play The Decision (1957). All three of these works, contrasted the “African” (meaning black) and Indian South African populations. Note the connection between Violaine Junod’s “Report on a Study of the Coloured ‘Social Elite’ in London” (1952) and Hilda Kuper and Fatima Meer’s “Indian Elites in Natal” (1956). Violaine Junod was close to both Hilda Kuper and Fatima Meer (Junod n.d.). Fatima Meer described the Kupers and Violaine Junod as her “most constant friends” during the Treason Trials in 1956 (Meer 2017, 169).

Junod, Violaine. n.d. “Violaine Junod Letters to Hilda Kuper, Correspondence from 1970s-80s.” Box 52. Folder 7. Los Angeles, CA: Hilda Kuper Papers, Box 52, Folder 7, UCLA Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library.

Meer, Fatima. 2017. Fatima Meer: Memories of Love and Struggle. Edited by Shamim Meer. Cape Town: Kwela Books.

Part 3: Hilda and Fatima’s relationship

Hilda met Fatima Meer in 1952 when Hilda moved to Durban, where her husband Leo Kuper, received a Sociology chair position at the University of Natal. It was Leo, the new head of the department, who allowed Fatima to rewrite her sociology honors exam (after she had been failed by a racist Afrikaner Nationalist lecturer); she passed with “flying colours” (Meer 2017, 150-151).

Fatima was Hilda’s research assistant for Kuper’s book Indian People in Natal (Kuper 1960, x). The Institute of Community and Family Health in the Newlands neighborhood in Durban funded this research (Meer 2017, 155). Fatima’s fieldwork notebooks in the Hilda Kuper Papers, elaborate the effect of Indian immigration to South Africa upon caste affiliation, marriage traditions, legally required medical care, and labor strikes. Meer also tracked and summarized the ship logs by sex, age, caste, religion, village, and marriage status (Kuper et al. 1953). In her autobiography, Fatima refers to “filling in dozens of these reporter’s notebooks” but unfortunately, she was dismissed after only a year from this position at the Institute of Community and Family Health because of her anti-apartheid activism and radicalism; Hilda and Fatima were both shocked (2017, 158). Hilda clearly used Fatima’s notes in Indian People in Natal in Chapter 1 regarding migration and Chapter 2 on changes in caste affiliation post-migration.

Kuper, Hilda, Fatima Meer, R. Singh. 1953. “Hilda Kuper Papers, Box 14 (Fatima Meer and R. Singh Fieldnotes).” Los Angeles: UCLA Special Collections.

Hilda conducted fieldwork in Durban in three Indian suburbs from 1953-1957 with funding from the Council for Social and Industrial Research. She worked with Indian health educators who were trained by the Institute of Community and Family Health including four women Miss N. Perumal, Mrs. Padmini Govindoo, Sally Naidoo and Violet Padayachee. In addition to Fatima Meer, Mrs. Radhi Singh assisted Hilda (Bank 2016, 218-221; Kuper 1960, x).

Bank, Andrew. 2016. Pioneers of the Field: South Africa’s Women Anthropologists. London, England: Cambridge University Press, International African Institute.

The Kuper home was a central site for anti-apartheid solidarity across racial lines. On November 9, 1952, Leo collaborated with the joint ANC-Indian Congress political rally at Red Square in Durban; he wrote about his experiences in Passive Resistance in South Africa (1955). Leo was arrested in 1956 with Alan Paton and four Indian Congress members for their participation in the “assembly of the Native” in the Gandhi Library Hall in Durban; this is where they launched a defense fund for the 156 Treason Trialists. Hilda was arrested earlier in 1956 with Fatima Meer at a women’s march protesting new laws that extended the pass system to “non-European” women (Bank 2016, 217–18). Also in 1956, the Kupers “solicited a loan” and “stood guarantor” for Fatima and her husband Ismail Meer, so that they could get the capital to build their house, since non-whites could not get loans at that time (Meer 2017, 163).

Hilda was “combative with non-progressive colleagues” and was excluded from a departmental research trip to Swaziland, despite her expertise (Russell 1994, 146). By the late 1950s, the apartheid police increasingly harassed Leo and Hilda, spies attended their lectures, and Leo was threatened with a banning order; eventually Hilda instigated their departure from South Africa (Golomski 2011, 4; Moran 1988, 198).

Russell, Margo. 1994. “OBITUARY: Hilda Kuper, 1911-92.” Africa 64 (1): 145–49.

Golomski, Casey. 2011. “Hilda Kuper, Anthropology, History.” In University of Swaziland, UNISWA, History Staff Seminar Series, 21. University of Swaziland, Department of Theology and Religious Studies.

Moran, Katy. 1988. “Hilda Beemer Kuper (1911- ).” In Women Anthropologists: Selected Biographies, edited by Ute Gacs, Aisha Khan, Jerrie McIntyre, and Ruth Weinberg, 194–201. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

In 1970, Hilda wrote to Fatima from Los Angeles to express that she was “so delighted” with Fatima’s book (Portrait of Indian South Africans, 1969) that she and Leo felt Fatima should submit it for a Ph.D.

“The photographs are fascinating and the text is rich in perception.”

Kuper, Hilda. 1970. “Hilda Kuper to Fatima Meer and Ismail Meer, March 20, 1970.” Los Angeles, CA: Hilda Kuper Papers, Box 41, Folder 9, UCLA Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library.

In closing, Hilda wrote, “There is so much to talk about that cannot be expressed in letters. We think of you very often and send you much, much love” (Kuper 1970). In her autobiography, Fatima wrote that Hilda Kuper “considered the manuscript so good that she canvassed the head of department to award me a doctorate for it” (Meer 2017, 186).

Part 4: The Decision

The Decision (1957) is a tragic play written by Hilda Kuper in which the female lead character is punished through death, for the patriarchal and racist hierarchical structure of her society. In this play, Savitree, a girl from a high caste Hindi speaking family in Durban, in Natal province, South Africa, fell in love with a Tamil Christian boy, Siva, whose family was from Southern India.

Their different ethnicities and religions, as well as the fact that Siva was active in the Indian National Congress and the passive resistance movement, marked Siva as “other” and unmarriageable (61). One version of the story closed when Savitree set fire to herself and died because her family forbade her to be with Siva (Kuper 1993, 63).

Kuper, Hilda. 1993. A Witch in My Heart: Short Stories and Poems. Edited by Nancy Schmidt. Madison: African Studies Program, University of Wisconsin–Madison. https://books.google.com/books?id=bh5aAAAAMAAJ&pgis=1.

In a different version of the play, Savitree sacrificed herself by marrying the man her family decided she should marry (Kuper 1957, 30–31).

Kuper, Hilda. 1957. “The Decision: A Contemporary South African Indian Play.” Durban Medical Students Drama Group. Los Angeles, CA: Sondra Hale Personal Collection, UCLA Anthropology Department, Haines Hall 391.

Directly before Siva heard the news of Savitree’s suicide (in the 1993 version) he told his activist friends that Indian South African families imprison their daughters in domestic roles, preventing their freedom. Siva’s friend Rajid Naidoo argued:

“African women are a major force in African politics, but few Indian women are active in political affairs.”

Hilda Kuper, 1993

This implied that the problem was within Indian culture, rather than South African culture as a whole. Siva’s friend Chetty remarked that the women should “free themselves” rather than waiting for men to do so, upon which Siva discovered that Savitree killed herself, causing the reader to wonder if this was Savitree’s way of “freeing herself” (Kuper 1993, 63).

In the 1957 version of the play, Siva’s words close the play:

“all I wanted is to be myself and let others be themselves.”

Hilda Kuper, 1957

He contended that Savitree should not have had to sacrifice herself for her family out of the “strength of her affection for others, for those who had brought her up.” Siva emphasized that her loyalty should not lie with her family alone but with the “family of the people of the world” (31).

Perhaps, this was Kuper’s message for unity rather than separation between not only Indian South Africans, but also all South Africans.

Intriguingly, Kuper revealed that she had never published the play because a few Indian couples confronted her after a performance of the play in Durban (by Indian medical students) to inform her they would sue her for writing about their families. Though she did not know these families Hilda

“realized that I had struck a very vulnerable center and Indians were already scapegoated for much of the antagonisms so sadly I put the manuscript aside” but she was revising it for publication in the months before her death (Schmidt 1993, 1, n.5).

Schmidt, Nancy J. 1993. “Introduction.” In A Witch in My Heart: Short Stories and Poems, 1–3. Madison: African Studies Program, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Hilda had written about a case very similar to the one she depicted in her play, in her 1960 book, Indian People in Natal (for which Fatima was a research assistant).

“By no means unusual is the case of the girl from an orthodox Hindi speaking family who fell in love with a Tamil boy; on discovering this, her parents married her to a man of their own choice. From the beginning the girl was most unhappy with her in-laws, and after one of her frequent visits home she threatened to commit suicide if forced to return to them.”

Hilda Kuper, Indian People in Natal, 1960, p. 136

The Decision echoes some of the findings from a paper about Indian elites in Natal, co-written by Fatima Meer and Hilda Kuper (1956). They described two primary elite groups: the protest and compromise elites.

“The protest elites, led mainly by intellectuals, identify with Non-Europeans and ‘oppressed people’ in general; the compromise elites operate as a defensive and exclusive minority” (Kuper and Meer 1956, 145).

Kuper, Hilda, and Fatima Meer. 1956. “Indian Elites in Natal, South Africa.” In Social Science Conference, University of Natal, Institute for Social Research, 129–45. Durban, Natal, South Africa: University of Natal, Institute for Social Research.

Siva was part of the protest elite, while Savitree’s family represented the compromise elites. Meer and Kuper found that original caste differences between Indian immigrants were fading because of the

“upward mobility of the ex-indentured and the downward pressure from the Europeans, and it appears that the Indian elite of the future will relate more to the Non-Europeans in general than to specific sectional groups.”

Kuper and Meer, 1956, p. 145

Interestingly, despite caste distinctions fading, ethnic differences were not, for example between Tamil, Telegu and Hindustani, which are clearly displayed in Hilda’s play since Savitree’s Hindustani family disapproved of Siva because he was Tamil (Kuper 1957; Kuper and Meer 1956, 130).

This article about Indian elites echoes (thought does not cite) Violaine Junod’s findings from 1952 about protest and compromise leaders among the “coloured” social elite in Britain. Compromise leaders were the intermediaries between white and black groups, serving as non-political token “coloured” spokespeople “on show” in a “zoo situation” within white organizations, which were “sympathetic” to “colonial” issues. Compromise leaders had no direct ties to either colonial nationalist governments or to policy makers and were seen as “acting white” (Banton 1960:151-153). In contrast, protest leaders had close links with colonial nationalist movements, denounced white racism, and held defiant attitudes toward whites supposedly “sympathetic” to the cause. Protest leaders were esteemed by “coloured” community members but disliked by whites (Banton 1960:152).

Banton, Michael. 1960. White and Coloured: The Behavior of British People towards Coloured Immigrants. 2nd ed. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

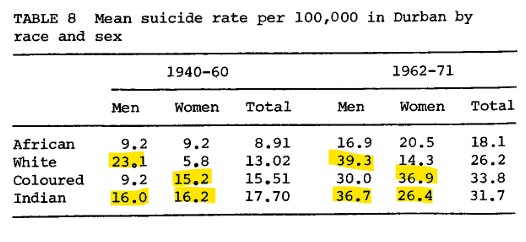

Fatima and Hilda’s findings related to Indians and suicide are interconnected.

“From the official figures of ‘self inflicted deaths’ published for Durban, the number of Indians who took their own lives is roughly the same as of Europeans, both being proportionately higher than the number of Africans and Coloureds; but when to these figures is added deaths in the category of ‘accidental burning’ – and burning is the traditional method of committing suicide among Hindus -the Indians outnumber all other racial groups.”

Hilda Kuper, 1960, p. 173

Conclusion

Fatima Meer and Hilda Kuper collaborated both political and theoretically, through their shared research interests. Hilda supported Fatima unconditionally (both financially and academically) while Fatima conducted foundational fieldwork which informed Hilda’s writing, both academic and creative (through Hilda’s play The Decision). Some of the key themes that they developed were the differences between Black women and Indian women in terms of involvement in South African politics. Fatima investigated the differences in suicide rates by race, gender, class and occupation in South Africa in the mid-20th century. Hilda explored a specific instance of suicide through her fictional play, which was based on the research she had conducted with Fatima. They also shared an interest in different types of elites, protest v. compromise elites, and they investigated how caste differences were becoming less important while ethnic differences were not, as evidenced in Hilda’s play, The Decision.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.