Dr. Abby Gondek, Morgenthau Scholar-in-Residence, FDR Library, Hyde Park, NY

PhD Global and Socio-cultural Studies, Florida International University

MA African and African Diaspora Studies, FIU

MA Women’s Studies, SDSU

This exhibit is part of the Morgenthau Holocaust Collections Project, a digital history and path-finding initiative to raise awareness of the FDR Library’s unique but under-explored resources for Holocaust Studies. The goal of the Morgenthau Project and my role as Scholar-in-Residence is to open new pathways for find-ability, using digital scholarship to explore these Holocaust-related records.

Overview/Abstract

This exhibit illustrates the Treasury department’s fight to issue a license to the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC or “Joint”) enabling aid to be distributed to Jewish children from France (1943-1944). Specific documents from the Morgenthau Diaries and the War Refugee Board are highlighted in order to bring attention to these expansive online resources offered at the FDR library. The documents demonstrate how the issue of rescuing children from France in 1943-1944 played a central role in the establishment of the War Refugee Board in January 1944 and the ongoing work of the War Refugee Board once it was established.

Some of the central themes explored are the consistent efforts of the State Department to block the Treasury Department’s efforts to issue licenses to Jewish organizations, the reluctance of neutral countries to accept the refugee children, the constant conditions or stipulations on their admittance and the insistence on “temporary asylum.”

Explanation of the making of this exhibit

This exhibit was initially designed as a presentation for an EHRI (European Holocaust Research Infrastructure) regional conference entitled “Escape and Rescue Routes-France, Belgium, Switzerland, Spain and Italy” in September 2019, and held at the Memorial de la Shoah, in Paris. The central question became: How was the issue of Jewish children refugees a central motivation for the development of the “Report to the Secretary” and the establishment of the War Refugee Board?

To prepare for the conference, I searched for the countries selected for the conference within an excel database of “refugee” related documents in the Morgenthau Diaries, created by Dr. Dottie Stone, Morgenthau Scholar-in-Residence, 2018-2019. The version of Dr. Stone’s database I used at the time contained approx. 500 entries however, more recently I discovered a version with 4305 rows (each row is one document).

Organization

The exhibit begins by providing background information (Section 1) so that the reader/visitor can better understand the history leading up to this particular story of children refugees. This background info includes the history behind the Gerhart Riegner telegram, the Bermuda conference, the Riegner License timeline and Breckinridge Long’s false testimony. Each of these events or issues have often been used to explain why the War Refugee Board (WRB) was created in January 1944.

The second section provides a different and under-explored explanation for the establishment of the WRB. The specific case discussed in this exhibit is the Joint Distribution Committee’s appeal for a license to provide aid and rescue to Jewish refugee children in France.

Then in Section 3, the body of the exhibit begins. The situation of the children is described from the fall of 1942 to the spring of 1943. The persistent themes of reluctance of neutral countries and insistence on only “temporary asylum” are introduced. The prohibition of financial transactions in “enemy territory” was the key blockage to the ability of Treasury to issue licenses to Jewish organizations like the World Jewish Congress (WJC) and the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC or Joint). This section also explores the State Department’s delay of the issuance of the license to the JDC.

The fourth section investigates the conflict between State and Treasury through State’s emphasis on the conflicts between two Jewish organizations (the Joint and the World Jewish Congress), John Pehle (the head of the War Refugee Board) felt this over-emphasis on conflict would hamper the rescue and relief effort.

Section 5, describes the period between February and March 1944 in which immobility persisted in the rescue effort. Britain was resistant to the idea of reserving permits for children to travel to Palestine, and created a series of conditions, making this migration practically impossible.

The last section explores documents which demonstrate that progress in rescue efforts began to be made in the spring and summer of 1944. A limited number of children were allowed entry into Spain and Portugal under the stipulation that the children would remain on a temporary basis only. Caribbean, Central and South American governments were asked to take refugee children but they often included conditions on this acceptance including allowing only a limited number of children refugees from specific countries of origin. Sometimes a country specified that they did not want Jewish children. Refugee camps were set up in North Africa to persuade Spain and Portugal to allow more refugees to enter and they were transferred to these camps to appease the “temporary asylum” policy. Isaac Weissman of the WJC proposed evacuating 6000 children from France but this plan was eventually discontinued by the WRB in September 1944 after France was liberated in August. By the end of 1944, there was a failed attempt to gain access to a boat to transport children from Marseille to Palestine though in the summer of 1944 there was a successful attempt to transport refugees from France, to Spain and then to Palestine. This section also discusses Jewish children refugees who remained in France.

(1) BackGround: The commonly-Used Explanations for the lead-up to the Establishment of the War Refugee Board

The lead-up to the establishment of the War Refugee Board (January 22, 1944) is a topic that has been explored by many scholars. The triggers of the creation of this organization have been traced to: Gerhart Riegner’s telegram, State department delays in issuing a license to the World Jewish Congress, the ineffective Bermuda conference, Peter Bergson‘s organizing and activism, the Gillette-Rogers Resolution, Breckinridge Long’s false testimony, and of course the “Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of this Government in the Murder of the Jews” developed by Treasury staff: Josiah DuBois, Randolph Paul and John Pehle. Each of these will be explained below. In the section that follows this one, an under-explored explanation will be presented, the focus of this exhibit, the efforts of the Treasury department and later the WRB to rescue Jewish children from France.

The Riegner Telegram (August – December 1942)

In August 1942, Gerhart Riegner, a German Jew who worked for the World Jewish Congress (WJC), in Geneva, Switzerland, reported the Nazi plan to exterminate Jews. Riegner wanted the message conveyed to Rabbi Stephen Wise (the head of the WJC), but at the American legation in Bern, Leland Harrison, the Minister to Switzerland, added a note that Riegner’s message was just a “rumor.” Subsequently, the European Desk of the State Department refused to forward Riegner’s message to Stephen Wise.

Thankfully, Riegner had also reported his news to the British consulate and so the message did get through. Wise then contacted Sumner Welles (who was at the time the Undersecretary of the State), who found corroborating evidence but told Wise that Welles could not publicize the information, though he encouraged Wise to do so.

This led to the December 2, 1942 Jewish communal day of mourning. Though Roosevelt acknowledged that Riegner’s report was true and agreed to issue a statement of warning and protest, his attention immediately went to North Africa where American troops had begun fighting.1 The Allied nations, including the US and the UK, issued a press release December 17, 1942 explicitly stating that “the German authorities were engaging in mass murder.”

- Rebecca Erbelding, Rescue Board: The Untold Story of America’s Efforts to Save the Jews of Europe (New York: Doubleday, 2018), 19-23.

Bermuda Conference (April 1943)

In April 1943, British and American delegates met to discuss refugee concerns in Bermuda. This was because they felt they had to show they were doing something but did not want to be tied to any specific follow-up action. Breckinridge Long (Assistant Secretary of State) suggested Bermuda because the press could be controlled there. None of the representatives from the State Department knew anything about refugee policy and were told that they could neither pledge money, food, clothing, nor propose to bring refugees to the U.S. These non-experts were also instructed to remind the British that Congress did not plan to expand American immigration quotas.

As the Washington Post wrote, “Hitler’s mass executioners will not wait while the delegates at Bermuda carry on their exploratory consultations, arrange for committees and subcommittees, pile up mountains of statistics and do nothing.”2 According to Yad Vashem, “the real reason the conference was called, however, was to shush the growing public outcries for the rescue of European Jewry without actually having to find any solutions to the problem.” Interestingly, “members of the Joint Distribution Committee and the World Jewish Congress were not permitted to attend.” In addition, “the Jewish aspect” was not allowed to be mentioned, nor was the “Final solution.”

2. Erbelding, Rescue Board, 31.

The Riegner License (WJC) timeline

From March-December of 1943, the State department had delayed the issue of a license to finance Riegner’s plan for relief efforts of Jews from France and Romania, including the evacuation of children from France to Spain and Switzerland.3

This timeline is part of the 18 page report given to Henry Morgenthau Jr. (HMJ), the Secretary of the Treasury, by his staff (Josiah DuBois, John Pehle, and Randolph Paul) on January 13, 1944.

March 13, 1943: WJC representative in London sent cable-possibility of rescuing Jews if funds available to WJC representative in Switzerland.

April 10, 1943: Sumner Welles cable to Bern legation, request to contact WJC representative in Switzerland, since Welles informed that this representative had important info re: Jews.

April 20, 1943: cable received from Bern re: financial arrangements in connection with evacuation of Jews from Rumania and France

May 25, 1943: State Dept cabled for “clarification” of the financial arrangements. Treasury department was not notified until June 25, 1943 (a month later).

July 15, 1943: conference held with State regarding this issue.

July 16, 1943 (only one day later): Treasury advised State to prepare to issue license.

December 18, 1943 (5 months later): license issued.

3. Erbelding, Rescue Board, 27-44.

4. Randolph Paul, “Report to the Secretary of the Acquiescence of this Government in the Murder of the Jews,” Morgenthau Diaries (MD) Vol. 693 (January 13, 1944): 212. Morgenthau Diaries will be referred to as “MD” in future footnotes.

Breckinridge Long Testifies (December 1943)

On December 10, 1943, Breckinridge Long’s testimony that the U.S. had accepted 580,000 refugees since 1933 was released by Representative Sol Bloom to the press. Long had testified in a private session on November 26. However, official statistics published by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, and then mined by the American Jewish Committee for “Hebrew” arrivals, revealed that refugee immigration was actually only 1/3 of Long’s estimate. State Department officials had (incorrectly) used the number – 580,000 – all year but Long had never checked the actual number. He blamed the “radical press” and “the Jewish press” who “turned their barrage against me.”5

Long’s testimony was a result of the efforts of congressmen Guy Gillette and Will Rogers Jr. (who allied with Peter Bergson and his Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe) to urge Roosevelt to develop a commission which would craft an action plan to save surviving Jews from Nazis. This was called the Gillette-Rogers Resolution.6 The resolution passed unanimously in the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee while Representative Sol Bloom, who headed the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, called for hearings at which Long testified on November 26, 1943.7 The goal of these hearings was to slow down the progress of the Gillete-Rogers resolution. Bloom felt, as the representative at the Bermuda Conference, that it would be a “blow to the Administration” to have the resolution on the “Floor of the House” since it would not be a “pleasant thing.”8

Breckinridge Long spoke on behalf of Cordell Hull from the State Department, claiming that the resolution and a new agency was unnecessary and redundant. With Sol Bloom’s support, Long agreed to make his remarks public because of the belief that they would convince the public that the resolution should not pass.

However, the opposite occurred once Long’s statements were published in the New York Times. Because his statistics were inaccurate, he and the administration were criticized by the media, mainstream Jewish organizations, and Congress. The full Senate was set to vote on the Gillette-Rogers resolution (that was Bergson-group backed) on January 24, 1944 and it was expected to pass.

Before this occurred, the Treasury department staff submitted a memo to Morgenthau (described above). Conversations between HMJ and his staff on March 8 and 16, 1944 explicitly link the Bergson group, the Emergency Committee, the Gillette-Rogers resolution and the establishment of the War Refugee Board.9

March 8, 1944 Meeting on “Jewish evacuation”

Present at the meeting are Pehle, DuBois, Henrietta Klotz and HMJ

HMJ: Let me just think out loud and see. After all, the thing that made it possible to get the president really to act on this thing –we are talking here among ourselves – was the thing that — the resolution [Gillette-Rogers] at least had passed the Senate to form this kind of a War Refugee Committee, hadn’t it? [Sol] Bloom was holding it…

Mr. Pehle: It was public pressure, too.

Mr. DuBois: It was more because of what you did than anything else, in my opinion.

HMJr: I had something to do with it, granted, but the tide was running with me.

Mr. DuBois: That is true.

HMJr: I think that six months before I couldn’t have done it.

Now, what I am leading up to is this: I am just wondering who the crowd is that got the thing that far.

Mr. Pehle: It is the emergency committee, Peter Bergson and his group.

5. Erbelding, Rescue Board, 45.

6. Richard Breitman and Allan Lichtman, FDR and the Jews (Belknap Press, 2013), 228-229.

7. Erbelding, Rescue Board, 44-45, 299.

8. Ansel Luxford, “Jewish evacuation meeting,” MD 693 (January 13, 1944): 198.

9. The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, “Rescue Resolution,” The Encyclopedia of America’s Response to the Holocaust.

(2) an under-explored explanation

There is another factor which should be explored to explain the impetus that led to the creation of the War Refugee Board: the case of the Joint Distribution Committee’s appeal for a license to provide aid to the Jewish refugee children in France. The Treasury department’s frustration with the State’s department’s inaction (and active prevention of action) in this case was also a significant trigger of the “Report to the Secretary.” In fact, the Treasury staff discuss the case of the Jewish children in France during the meeting in which they present their report to Morgenthau.10

10. “Jewish evacuation” meeting, MD Vol. 693 (Jan. 13, 1944): 194.

(3) Jewish refugee children

From the Fall of 1942 until June of 1943, 4000 children were deported from France to “unrevealed destinations” in “locked” and “windowless box cars,” 60 children to 1 car, without water, food or proper hygiene. Germans ordered the French police to complete a census of 6000 “abandoned” children in France (5000 were Jewish, 1000 were Spanish) who were hidden in private homes by Protestant and Catholic organizations. Up until August 1942, the Oeuvre de secours aux infants (OSE) used legal means to place refugee children in its children’s homes in France. However, during August 1942, “thousands of foreign Jews, including children, were taken from internment camps or rounded up throughout the southern zone and were sent to the occupied zone to face deportation to ‘an unknown destination.’” OSE began to operate using clandestine methods (extra-legal) including using church networks to place children in the homes of the general population. In April 1943, OSE began smuggling children to Switzerland and then later, to Spain. This was possible because of collaboration with the French Jewish Scouts, the Zionist Youth Movement, and the Armée Juive. The Joint Distribution Committee funded this smuggling effort.11

A theme emerged in this cable, common in other documents analyzed: everyone seemed “reluctant” to “receive and care” for the children. In this case it was the Swiss and Spanish who were “reluctant” because “transport and concealment” were becoming more dangerous with the increase of the border police. This cable reported that nothing had been done to help the children since February 11, 1943.

There were delays upon delays, in which months (and years) went by and nothing (or very little) would be done. In addition, Section 2 of this cable illustrates another theme, which is that if countries (in this case Switzerland and Spain) considered taking Jews it was only on a temporary basis- “temporary asylum” – and only if refugees would be “subsequently disposed” of elsewhere, meaning that some other country would have to take them.12 This theme appeared many times as a reason why neutral countries would not accept Jewish refugees; the country was not guaranteed that the Jews would go elsewhere after the war.

11. Renée Poznanski, “Reflections on Jewish resistance and Jewish resistance in France,” Jewish Social Studies 2, no. 1 (1995):142-144.

12. Leland Harrison (Minister to Switzerland) to Cordell Hull (Secretary of State), “Cable 3465,” Morgenthau Diaries Vol. 691 (June 9, 1943): 73.

“trading with the enemy”

The lack of financial resources to transport and support the children refugees was a central concern.13 Randolph Paul argued that the primary problem was that the U.S. government prohibited financial transactions with people in “enemy territory” without exception.

Paul contended that this “trading with the enemy” policy needed to be re-considered so that “exceptions can be made” to facilitate “relief” to “oppressed groups.” This memo was a proposal that would give defined, responsible and experienced groups permission to bring relief to refugees in enemy territory under certain conditions (and on a case by case basis). The conditions were that there must be no benefit to the enemy and that the base of operations should be a neutral country. Even though Paul expressed the desire to assist, this assistance could NOT be unconditional, and was extremely measured and cautious.

This is part of the theme of delay and consistent blockages which prevented relief over months and years. Paul seemed to err on the side of helping the refugees, even if the enemy might potentially benefit. He also used phrases here which reveal his position against the policy that the US should not do anything that could potentially aid the enemy. For example, the selection of the term “annihilation” and “slaughter” likely triggered emotional reactions in the reader (Morgenthau), causing him to side with the refugees.

13. Randolph Paul to Henry Morgenthau Jr., “Treasury Department Inter-Office Communication,” MD Vol. 688I (August 23, 1943): 24-30.

License issued to JDC

On January 3, 1944, a license was issued to the Joint Distribution Committee permitting the Joint (JDC) to remit $200,000 to Switzerland in order to “bring relief to several thousand homeless and abandoned children in France.”

Randolph Paul clarified that because of the urgency of this matter, the license had not been cleared with the State Department nor the British government. He added that the State Department had been asked to cable the text of the license to Bern (Switzerland) to inform the Legation there as well as the JDC representative in Switzerland, Saly Mayer. The legation in Bern had been asked to be proactive in facilitating operations under the license.

By 3:40 pm the next day, on January 4, 1944, the cable had still not gone out from the State Department and was sitting on William Riegelman’s desk. Riegelman worked for Breckinridge Long at the State Department and was HMJ’s cousin. John Pehle wanted the last paragraph to state that both State and the Treasury approved the license and that all “reasonable steps” should be taken to facilitate the license. HMJ set the deadline at 5:31 pm (sunset) that evening and emphasized that there should be “no damn fooling.”14 Long had told Riegelman that because of the familial tie between HMJ and Riegelman, “they’ll be less suspicious of us over in Treasury.”15 Pehle believed that by giving State a deadline by which to send the cable “it puts them right in a spot. I mean, if they don’t want to say they approve this program, why they ought to have to come out and say it.”16

14. Henry Morgenthau Jr. to John Pehle, “Transcript of Conversation,” MD Vol. 690 ( January 4, 1944): 92.

15. Morgenthau, “Transcript” MD Vol. 690: 93.

16. Morgenthau, “Transcript” MD Vol. 690: 94.

(4) Treasury v. State

On January 5, 1944 in a meeting on “Jewish evacuation” members of HMJ’s staff discussed conflicts they faced with issuing licenses to Jewish organizations because of State department delays.

At several points in John Pehle’s initial summary of events he described ways that the State Department had caused delays. For example, Riegelman claimed he could not send the cable (regarding the license for the JDC) without clearing it with State first. He also claimed he knew nothing of the operations described in the cable, which Pehle found curious since what Pehle knew had come from the State Department files.17

17. John Pehle, Transcript of meeting on “Jewish evacuation,” MD Vol 691 (January 5, 1944): 55.

Pehle referred to the August 26, 1943 memo (above) that HMJ approved and that was sent to State. Pehle then elaborated: “it got caught at State in that same difficulty that WJC [World Jewish Congress] was caught in”; in other words, the State department continued to cause delays to the processing of these licenses.18 Pehle explained that the JDC had remitted money to its agent in Switzerland (Saly Mayer) without a formal license.

A letter from the JDC had been sent to State but State neglected to forward it on to Treasury, though a copy was sent directly by the JDC to the Treasury Department; this was another piece of evidence that State was blocking information from reaching Treasury.19

Pehle thought that the cable (with the license for the JDC) would not need to go through Cordell Hull since it didn’t require the approval of the State Department. HMJ thought Hull would without a doubt approve it. Ansel Luxford hypothesized that “they may kick it around before it gets to him though”; HMJ stated he wanted to be informed when the cable left the State Department.20

18. Pehle, Transcript, MD Vol 691: 57.

19. Pehle, Transcript, MD Vol 691: 58.

20. Transcript of meeting, MD Vol. 691: 62.

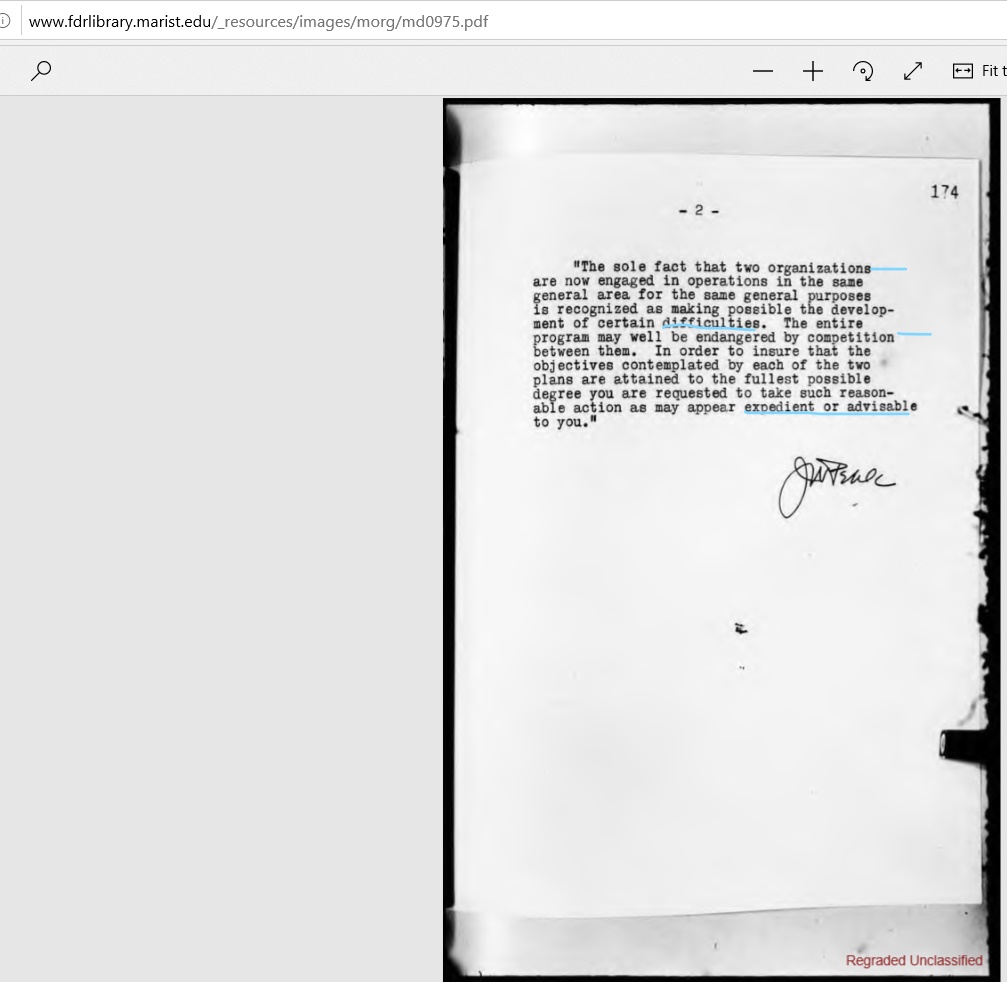

The following day, January 6, 1944, the Treasury department learned that the text of their license to the JDC had been sent to Leland Harrison in Bern, but Riegelman had added an introductory message to Harrison, which elaborated the differences between the WJC (only permitting evacuation procedures) and the new JDC license (which included both relief AND evacuation).

This cover letter also emphasized that because these two organizations did similar work in the same area they could develop “difficulties” and “competition” which could endanger the whole operation. This message asked Leland Harrison to take action that he felt was “expedient.”

After hearing about Riegelman’s introductory message to the license from Florence Hodel, Pehle expressed to Riegelman that he was “very disturbed” that this cable went out without clearance from Treasury. Riegelman insisted multiple times that he was not the sole actor behind this cover letter and that it had been a unanimous decision in State with the approval of Cordell Hull.21 While Riegelman (and State) contended that “friction” between the two Jewish agencies (WJC and JDC) could hamper the benefits of the license, Pehle, and the Treasury, felt that the new language (unapproved by Treasury) would lead Leland Harrison to arbitrate between the agencies. This was exactly what Pehle did NOT want. Pehle felt it would lead Harrison to require clearance of all transactions first, interfering with the ease of operation for both of these organizations, rather than helping them.22

21. William Riegelman, “Conference Memorandum,” MD Vol. 691 (January 6, 1944): 176-177, 180.

22. John Pehle, “Conference Memorandum,” MD Vol. 691 (January 6, 1944): 178-179.

(5) February And march 1944- immobility

As of February 18, 1944, there was no promise of exit permits from the German authorities for Jewish children to leave France, despite the Swiss government’s appeal. IF the exit permits were granted, there would be negotiations with Spain and Portugal about getting the children through those countries so that they could go “overseas.” AWG Randall (in the Foreign Office in the UK) felt that it was more “practicable” that the children be directed through Spain and Portugal rather than through Switzerland.

The UK would not be saving or “freezing” a portion of permits for children refugees from France to enter Palestine because the Foreign Office viewed this as only a “hypothetical” situation and the children “may not be able to use them.” The Foreign Office claimed that they did not want to “reduce the stock available for the regular allocations which are made in agreement with the Jewish Agency.”

There were a series of conditional situations in which the British might be willing to set aside spots in Palestine for the children: (1) IF Germany gave the exit permits, (2) IF asylum in other countries aside from Switzerland was “insufficient”, (3) IF it was “impracticable” to transport the children to those countries, and (4) IF the Swiss government imposed conditions on the acceptance of the children such that the children would have to be taken elsewhere post-war. After all those conditional situations were met, the Swiss government could apply to the Intergovernmental Committee, and only then would the British government consider placement of the children in Palestine.

Overall the impression left is that the British government aimed to prevent the children from going to Palestine at all costs and more broadly, that the British government did want to take any responsibility for what would happen to these children.

(6) Some progress begins to be made

Issuing immigration visas to refugee children

In March and April 1944, the US government authorized American consular officers in Switzerland to issue up to 4,000 quota immigration visas to refugee children (up to age 16) who had or would arrive in Switzerland from France during the first six months of 1944. The purpose was to “cause the Government of Switzerland to give refuge to additional refugee children from France,” where there were an estimated 8-10,000 abandoned or orphaned children. The WRB wanted to assure the Swiss government that orphaned and abandoned children escaping into Switzerland would not remain there. The WRB made a similar authorization of 1000 visas to refugee children escaping from France to Spain and Portugal. Visas would be issued without regard to religion, nationality, whether the children had relatives in enemy, or enemy-occupied territory, or their ability to access transportation to the U.S. The US authorization detailed that the visas should be renewed until the children could be transported to the US. Subsequently the US government asked countries (including the Caribbean, Central and South America) if they would be willing to accept and care for these refugee children from France (and other occupied territories) once they had escaped into Switzerland or Spain/Portugal. The War Refugee Board offered to make arrangements with agencies which could provide the funds for transportation, maintenance, education and welfare for the children.23

The following is a record detailing which countries agreed to take how many children refugees, under which conditions. This list references the specific cable numbers and the corresponding dates. Interestingly, the “conditions” for Costa Rica and El Salvador state: “Provided all costs borne by War Refugee Board.” Guatemala, Honduras, and Peru specify the nationality preferred: French and Belgian (for Guatemala and Peru) and Polish and French (for Honduras).

23. The following are in WRB Series 10, Box 117, History of War Refugee Board with Selected Documents, Vol. II: Hull to the American Legation in Bern, Switzerland, Telegram no. 891, March 18, 1944, Folder 2, pp. 562-563; WRB (via Hull) to the Minister at the American Legation in Canberra, Australia, No. 40, April 12, 1944, Folder 2, p. 567; Hull to American Embassy in Madrid, No. 1008, April 12, 1944, Folder 3, pp. 686-687; Cordell Hull to Ambassadors at Panama, Habana, Ciudad Trujillo, Bogota, Lima, Santiago, Montevideo and Mexico, D.F., Circular Airgram, April 15, 1944, Folder 2, p. 570; Walter Thurston, US Embassy in San Salvador to Dr. Avila, Enclosure no. 1, April 25, 1944, Dispatch No. 1531, May 4, 1944, Folder 3, pp. 580-583.

The following are examples of the information conveyed in the cables listed in the table above.

April 27, 1944: Honduras agreed to receive a maximum of 50 children and voiced a preference for “Polish, French or some other class of children would be more acceptable than Jews.”24

May 2, 1944: A.R. Avila (El Salvador) conveyed a message that “in principle” El Salvador would “grant refuge to [100] orphaned or abandoned children now within the territory occupied or controlled by the enemy” however Avila wished to know if the WRB would pay for the construction of a building to house the children, as well as money to pay for feeding and educating them.25

May 4, 1944: the Dominican Government offered to accept between 1000-2000 refugee children up to the age of 16. Private institutions subsidized by the state would provide care.26

May 11, 1944: Guatemala agreed to receive 100 children “but would prefer… these children be selected from French and Belgian refugees.”27

On June 16, 1944, the Costa Rican Patronate Nacional de la Infancia, an agency responsible for orphaned children, offered to accept 1000 refugee children into private families under the condition that they would be allowed to stay permanently with the families since these families would be “reluctant to accept children who might be returned to Europe after the war.” The families would take care of the expenses for the children but the WRB would need to pay transportation costs.28

On August 22, 1944, President Getulio Vargas of Brazil approved a plan to bring 500 Jewish refugee children from France to Brazil as long as Brazil would not incur the expense of transportation and maintenance.29

September 5, 1944: Cuba agreed to offer lodging to 1,000 refugee children from France and Hungary.30

September 15, 1944: Ecuador agreed to accept approximately 300 orphaned or abandoned children from Europe under the condition that the WRB would furnish the funds necessary.31

24. Faust at the US Embassy in Honduras to Secretary of State, Airgram no. 165, April 27, 1944, WRB Series 10, Box 117, Folder 3, Vol. II, p. 587.

25. Walter Thurston, US Embassy, San Salvador, El Salvador to the Secretary of State, No. 1531, May 4, 1944, including copy of letter from Avila to Thurston from May 2, 1944, WRB Series 10, Box 117 History of War Refugee Board with Selected Documents, Vol. II, Folder 3, pp. 580-581.

26. Robert Newbegin at the American Embassy, in Ciudad Trujillo to the Secretary of State, telegram no. 219, May 4, 1944, and no. 240 of May 19, 1944, WRB Series 10, Box 117 Vol. II, Folder 3, pp. 576-577.

27. Boaz Long, US Embassy in Guatemala to Secretary of State, No. 1104, May 15, 1944, Carlos Salazar of the Secretariat for Foreign Affairs to Boaz Long the Ambassador to the US in Guatemala, No. 6130, Enclosure No. 2 to dispatch no. 1104, May 11, 1944, WRB Series 10, Box 117 Vol. II, Folder 3, pp. 584-586.

28. Fay Allen Des Portes at the American Embassy in San Jose, Costa Rica to the Secretary of State, Airgram no. 390, June 16, 1944, WRB Series 10, Box 117 Vol. II, Folder 3, p. 573.

29. Jefferson Caffery in Rio de Janeiro to Secretary of State, Airgram no. 1568, August 22, 2944, WRB Series 10, Box 117 Vol. II, Folder 3, p. 572; Section V.E. Cooperation with Other Governments: Others, WRB Series 10, Box 117 History of the WRB with Selected Documents, Vol. I, Folder 1, p. 396, note 3 refers to dispatches no. 14561 and 14890 from Rio de Janeiro, February 12, and March 11, 1944.

30. Garret G. Ackerson, US Embassy, Habana to Secretary of State, Airmail no. 7845, September 7, 1944; Enclosure no. 2 to dispatch no. 7845, September 5, 1944, a translation from the Ministry of State, WRB Series 10, Box 117 Vol. II, Folder 3, pp. 574-575.

31. James W. Gantenbein, US Embassy in Quito, Ecuador, to Secretary of State, No. 2140, Sept. 15, 1944 and enclosure no. 2 to dispatch no. 2140, a translation, WRB Series 10, Box 117 Vol. II, Folder 3, pp. 578-579.

Evacuations from France, through Spain and Portugal

Refugee Camps in North Africa

Because of demands from the Portuguese and Spanish governments to remove refugees from their jurisdiction as quickly as possible, the War Refugee Board collaborated with the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) to run camps in North Africa including Fedhala (Lyautey) outside Casablanca, Morocco, and Philippeville in Algeria.32 According to Rebecca Erbelding (2018), Camp Fedhala or Marechal Lyautey (an abandoned military installation ten miles outside Casablanca) was initially envisioned as a refugee camp at the Bermuda conference in 1943 as a motivation for Spain to permit more refugees to enter Spanish borders knowing they could be sent elsewhere. However, 5 months after the WRB itself was created, the camp still had not opened. Few refugees wanted to go there and preferred to stay in Spain. Moses Beckelman, a UNRRA social worker who had formerly been affiliated with the JDC, was the camp’s first director. In June 1944 the WRB finally evacuated 573 refugees from Spain to Fedhala.33

As early as February 1944, the WRB discussed with Ambassador Hayes, the need to evacuate Jewish refugees from Spain (who had come from France) to Camp Lyautey. The Board felt this was of the utmost importance to encourage Spain to allow more refugees to enter. Refugees should be held (involuntarily if necessary) in reception centers or camps until they were transferred to North Africa.34 The “French refugee movement” had already been successful in evacuating refugees to North Africa and 567 Jewish refugees were evacuated from Spain to Palestine with the assistance of the Joint on January 25, 1944 on a Portuguese ship.35 As of March 27, 1944, of the 1550 refugees who were currently in Spain, 865 had applied for Lyautey, but French authorities rejected 10 percent making the total likely to be 775.36

According to a report from August 1944, the “Fedala” camp was made up primarily of children and elderly. Though later in the report, the number of children was revealed to be “about 65” and the total inhabitants approximately 650 (as of August 17, 1944). The author of the report referred to a convoy of French refugees who had recently arrived with about 30 “gypsies.” The report detailed the make-shift school at which children learned in French, had access to a playground, balls for games, and school supplies like blackboards, chalk, pencils, rulers, paper, and glue. There were five teachers, though only one had previous teaching experience, the others had been private tutors.37

In September and October 1944, the WRB began discussing the possibility of sending refugees in Portugal to Fedhala, where they would supposedly be “better cared for” than they would be if they stayed in Portugal. The children would have access to “excellent schools,” unavailable in Portugal. The theory was that refugees were more likely to immigrate somewhere else after the war if they were sent to Fedhala than if they remained in Portugal. This was of course more desirable to the Portuguese government which did not want to be a “final destination” for these refugees. Since the WRB planned to remove its representative from Portugal as of December 1, 1944, Edward Crocker at the American Embassy in Lisbon was concerned that the refugees in Portugal would have no representation, especially since many aid organizations would be leaving as the war ended.38

32. Section VI.C. Cooperation with International and Governmental Agencies: UNRRA, WRB, Series 10, Box 117, Vol. I, Folder 1, p. 421.

33. Erbelding, Rescue Board, 78-80, 168.

34. Cable to Ambassador Hayes, February 9, 1944, Secretary of State to American Embassy, Madrid, Cable no. 799 [number is blurred], March 25, 1944, WRB Box 46, Folder 14, “Program with Respect to Relief and Rescue of Refugees: Evacuation to and through Spain (and Portugal)”

35. Secretary of State to American Embassy, Madrid, Cable no. 463, February 18, 1944, Hayes to Secretary of State, Airgram no. 39, January 27, 1944, WRB Box 46, Folder 14.

36. Norweb to Secretary of State, including message from Joseph Schwartz to Moses Leavitt, Cable no. 919 (number blurred) March 27, 1944, WRB Box 46, Folder 14.

37. Carmel Offie, Foreign Service Officer, for the the US Political Advisor, Allied Force Headquarters, to the Secretary of State, Despatch No. 775, September 22, 1944. Enclosure, Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, Representative with the French Provisional Government, Algiers: Gouverneur V. Valentin-Smith, August 28, 1944. Transmitted to Carmel Offie by R.L. Cochran, Principal Representative of the UNRRA, Mediterranean Theater. WRB Box 46, Program with respect to relief and rescue of refugees (PWRTRAR) Evacuation from Spain to Lyautey Folder 1, pp. 1-2.

38. Norweb to Secretary of State, No. 2875, September 14, 1944, Edward Crocker, American Embassy, Lisbon, to Secretary of State, No. 1071, October 16, 1944, WRB Box 46, Folder 14.

Isaac WEissman’s proposal

In April 1944, Norweb conveyed Isaac Weissman’s plan to bring “6000 hidden children clandestinely out of France through Spain to Portugal and 3000 others registered in France” and requested the financial and practical support of the WRB without which the plan would fail. The WJC intended to send the children to Palestine, which was easier than sending them to the U.S. because of the cost and also the availability of visas. However: “This presents a problem as there will be a conflict between Zionist and non-Zionist Jewish organizations regarding ultimate destination of children.” Weissman requested directives from the WRB.39

By May 9, 1944, children began to arrive in Portugal. Isaac Weissman (WJC in Lisbon) provided specific names of the children and asked Rabbi Stephen Wise to locate any relatives in New York. Eighty children were being housed in “seaside accommodations.” The WJC also helped non-Jewish children: “Our sincerest wish be helpful to non-Jewish children.” Both the American and British embassies intervened on the behalf of the WJC so that “now rescued children can regularly enter Portugal, not exceeding simultaneously 300.” Spain would allow up to 500 children to enter in transit to Portugal; reception centers were set up in Barcelona and Madrid. 600 non-Jewish children would be allowed to enter and reside in Spain until the end of the war.40 The US Embassy in Portugal reassured the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs that “every effort” would be made “secure visas and transportation” for the children to depart to other destinations “in the shortest possible time.”41

On May 29, 1944, Joseph Schwartz (JDC) provided specific numbers of adults and children who had arrived in Spain (200 total newcomers). 500 children had arrived in Switzerland from France in the past two months. The JDC could not accommodate large numbers of new arrivals because of “physical and other difficulties.” He conveyed the difficulty of legalizing newcomers, but that the JDC had prevented the majority from being sent to camps and prisons.42 Even though this was comparatively good news, it is important to note the limited number of children allowed entry into Portugal and Spain at one time and at all, and the condition that the children would remain on a temporary basis only.

On July 13, 1944 representatives of the Joint (Robert Pilpel), World Jewish Congress (Weissman) and the Jewish Agency for Palestine (Eliyahu Dobkin) met at the American Embassy in Lisbon with James H. Mann and Robert C. Dexter serving as intermediaries for the WRB. These representatives agreed to cooperate with each other and share information with representatives in Portugal. They would form a Spanish rescue committee, headed by Jules Jefroykin (JDC), Joseph Croustillon (WJC) and David Sealtiel (Jewish Agency for Palestine). The representatives present at the meeting agreed that refugees entering Spain would be turned over to the JDC while all children would be sent to Portugal and turned over to the Youth Aliyah Committee of Portugal. Peretz Lichtenstein, Pilpel, and Weissman would serve only as individuals to this committee, not as representatives of their respective organizations and they would report to Henrietta Szold, the head of Youth Aliyah in Jerusalem.43 On August 24, one day before the liberation of Paris, Norweb reported that Crustillon [sic] “rejects appointment and refuses to be bound by it.” Subsequently, the JDC considered the July agreement to be “void”; the Jewish agency acquiesced. However, because of the “military situation” this issue did not concern Norweb and he felt that the “situation” in both Portugal and Spain could be cleared easily.44

July 20, 1944: 60 children were sent from France, to Spain and then to Palestine (there were a total of 700 refugees but only 60 were children). The goal was for these youth to join the Jewish military in Palestine or to reach North African and the French armies. “This is a very difficult expedition, very dangerous and very costly.” There were five accidents (implying that five people died in transit). The Federation of Jewish Societies took care of 400 children in Paris and had sent children out of France (aside from those sent to Spain). 1000 people (does not specify whether they were children or not) were sent abroad to places other than Spain.45

On July 29, 1944, the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees (ICR) expressed how difficult it was to get children out of France. It wanted to receive assurances that the US would indeed take 5,000 children and that Canada would take 1,000.46 The ICR also stated that there would be homes for 3,000 children if they could reach Spain or Portugal. However, the ICR believed that priority should be made for those children escaping Hungary (where deportations had begun in May 1944). Though the WJC could not guarantee funding, the JDC could assure maintenance of the children for a short period. ICR seemed unsure if Weissman (WJC) was in conversation with the Joint, but thought that this would be “desirable.” The International Red Cross would approach the French authorities about getting the children out.47

By August 10, 1944, the War Refugee Board felt that the WJC’s proposal (called “Dobkin-Weissman”) to evacuate 3000 children from France was unlikely to succeed based upon previous unsuccessful attempts. Instead the WRB decided to extend the 5,000 visas, which had previously only been available to French children, to Hungarian children or those from other countries in Europe.48

On September 2, 1944 efforts to bring children or adults from France through Spain were discontinued as a result of “recent military developments in France.” (Paris was liberated August 25, 1944.) Instead, the JDC concentrated on transporting refugees to Palestine who were already in the Iberian Peninsula or Tangiers (and who had arrived recently from France) and who held Palestinian visas. The Joint awaited news about a potential ship from Spain as well as from Portugal that could carry Jews (including children) to Palestine. There was pressure on the WRB to enact these evacuations as soon as possible to appease the Portuguese government.49

On November 28, 1944, a newspaper article (New York Daily Mirror, see above) depicted how 5,000 Jewish orphaned children in France were saved by “professional smugglers,” Spanish and French women who took the children through “forbidden military zones.” The World Jewish Congress claimed “full credit” according to its delegate from Lisbon, Portugal, Isaac Weissman. However, since the WRB discontinued its program to evacuate children from France it is unclear when and how Weissman smuggled these 5000 children out and if 5000 was an accurate number.

According to Robert Dexter, the WRB representative in Portugal, Weissman and the WJC were known for being “keen on publicity with their name attached.” Dexter warned that this endangered the whole rescue project.50 Joint representative, Laura Margolis, told James Mann (Assistant Executive Director of WRB) that they feared a joint effort between the JDC and WJC would endanger rescue work because the WJC would use publicity in the Jewish press. When Mann asked Weissman not to publicize rescue work, Weissman claimed that the WJC never used publicity but that the JDC did.51

From other documents in the WRB papers, there is evidence of much fewer rescues. For example, there were 500 Jewish refugees in Portugal as of October 16, 1944.52 As of August 5, 1944, a total of 402 individuals had been rescued and brought to Spain, according to Joseph Schwartz of the JDC.53

In a World Jewish Congress report of rescue activities submitted by A. Leon Kubowitzki, as of September 1944, 1350 children and young people had reached Switzerland, 70 reached Spain, 700 evacuated to Spain and 700 were still hidden in France. Robert Dexter wrote to Weissman in October 1944 that it was “largely, if not entirely” Weissman’s “initiative” that the “beginnings were made” to bring both children and adults out of Spain and into Spain and Portugal. Dexter consoled Weissman “It is not your fault that this number was not vastly greater, but the hundreds who did come through, whether under the auspices of your organization or in any other way, owe you and the World Jewish Congress a deep debt of gratitude…”54

The New York Daily Mirror article is further put into question considering a message from Lazar Gurvitch to Leon Wulman (both from the OSE: Oeuvre de Secours Aux Enfants or Children’s Aid Society) received by the WRB on October 7, 1944: “We shall keep in France during the next few months at least 5,000 children, most of whom have been abandoned. About 2,000 of these children together with families are being helped.” The OSE (funded by the JDC, and with the collaboration of Joseph Schwartz) had begun to re-open children’s homes, provide medical and social consultations, and receive food and medical supplies. Also a search bureau was set up to re-connect parents with their children. On November 3, Jules Defroykin (JDC Director, France) sent a report to Major Paul Warburg (US Embassy, Paris) detailing the situation of Jews in France. This document reported that 5,000 children were entrusted with French families in the countryside, while 3,000 were sent to Switzerland. In addition, “the Jewish organizations” provided for 8,000 children “disseminated throughout France” who were orphaned or whose parents were deported. This calls into question whether Isaac Weissman and the WJC really did smuggle 5000 children out of France to Spain and Portugal.55

According to Renee Poznanski, once “foreign Jews,” including children were either removed from internment camps or “rounded up” throughout the southern zone of France and sent to the occupied zone to be deported (in August 1942), the strategy of the OSE (Oeuvre de secours aux enfants) drastically changed from solely using legal means, to clandestinely placing refugee children in the homes of the “general population,” with the assistance of church organizations. Because of an underground network of Jewish organizations like the French Jewish Scouts, and the Zionist Youth Movement, the OSE was able to “smuggle” children into both Switzerland and Spain. Children were cared for in Spain because of the Armée Juive. Importantly, Poznanski notes that it was the JDC which funded the smuggling and specifically mentions Jules (Dika) Jefroykin and Maurice Brenner, the JDC reps in France.56

A different article published in the NY Post in September 1944 reported that between 12,000 and 15,000 children in France were smuggled out to Switzerland, where “American Jewish organizations” supported them.57

39. Norweb to Secretary of State, Cable no. 1168 Section One and Two, April 19, 1944, WRB Box 46, Folder 14; Box 118 History of WRB with Selected Documents, Vol. II, Folder 4, p. 711; Morgenthau Diaries Vol. 722: 354-355.

40. Norweb to Cordell Hull, Cable No. 1395, page 2, May 9, 1944, WRB, Box 46, File 15.

41. May 10, 1944, No. 494, Edward S. Crocker to Cordell Hull, May 8, 1944, No. 309, despatch to Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Portugal, WRB, Box 46, File 15.

42. John Pehle to Moses Leavitt, May 29, 1944, WRB, Box 46, Folder 15: Evacuation of Children from France to Spain and Portugal- JDC.

43. Memo of meeting between Dobkin, Pilpel, and Weissman with Mann and Dexter, July 13, 1944, Lisbon, WRB Box 118 History of War Refugee Board Vol. II, Folder 4, pp. 713-715.

44. Norweb to Secretary of State, Cable no. 2612, WRB no. 162, August 24, 1944, WRB Series 2: Projects and Documents File: January 1944-September 1945, Box 37, Folder: Cooperation with other Governments – Neutral Europe – Portugal, page 22 of 136 in file.

45. Report of the Federation of Jewish Societies in France, July 20, 1944, forwarded to John Pehle by I.A. Hirschmann in Istanbul, August 15, 1944, p. 2, WRB Box 10, Folder 18: France.

46. John Winant to Cordell Hull, Cable no. 6054, July 29, 1944, p. 1, WRB, Box 46, Folder 15.

47. Winant, Cable no. 6054, p. 2

48. Stettinius to the American Embassy in London, text of cable from War Refugee Board, Telegram no. 6323, August 10, 1944, WRB, Box 46, Folder 15, references cable no. 6054.

49. Series of cables from September 2, 1944, August 29, 1944 in WRB Box 46, Folder 14: Cable from Joseph Schwartz (JDC rep in Lisbon) forwarded by Pehle to Moses Leavitt (JDC in NYC) September 2, 1944; Norweb in Lisbon to the Secretary of State containing the message from Schwartz to Leavitt, Cable no. 2662, August 29, 1944; Norweb to the Secretary of State, cable no. 2657, August 29, 1944; Pehle to Dexter, Cable no. 2331 August 24, 1944.

50. Robert C. Dexter to John Pehle, “Preliminary Report on Activity for Refugees in Portugal for War Refugee Board,” MD Vol. 726 (April 26, 1944): 233.

51. James Mann, “Report of James H. Mann on Trip to Portugal and Spain,” pages 42-43, August 30, 1944, WRB, Series 5: Records Formerly Classified as Secret June 1944-August 1945, Box 79, Folder 6: Reports of Trip to Spain and Portugal (Mr. Mann).

52. Edward Crocker to Secretary of State, No. 1071, WRB Box 46, Folder 14.

53. Norweb to Secretary of State, conveying message from Joseph Schwartz to Moses Leavitt, Cable no. 2418, WRB, Box 46, Folder 14.

54. A Leon Kubowitzki, World Jewish Congress, Rescue Department Survey of the Rescue Activities of the World Jewish Congress 1940-1944, Submitted to the War Emergency Conference, Atlantic City, Nov. 26-30, 1944, pages 29-30, WRB, Series 1: General Correspondence, Box 19, Folder 74: James H. Mann

55. Hull to American Embassy, Paris, (original from Julius Brutzkus and Leon Wulman of the American Committee of the OSE to Eugene Minkovsky, chair of OSE Paris) Cable no. 200, October 20, 1944; Pehle to Wulman (original message from Lazar Gurvitch, the General Secretary of the World OSE Union), October 11, 1944 (October 7, 1944); Jules Jefrokykin to Major Paul Warburg, November 3, 1944 and report, pp. 2, 6, WRB Box 10, Folder 18: “France”

56. Renée Poznanski, “Reflections on Jewish resistance and Jewish resistance in France,” Jewish Social Studies 2, no. 1 (Autumn 1995): 142-144.

57. September, 15, 1944, WRB Box 10, Folder 18: France.

Late 1944, Early 1945

In November and December of 1944, the WRB attempted to make arrangements for Jewish refugee children to travel from Marseilles to Palestine via boat. This proved to be a frustratingly complicated arrangement. Some possibilities which were discussed were to use military ships or private yachts but these ships would supposedly need to undergo alterations to be able to accommodate the 3,000 children in need of transportation (2,000 from France and 1,000 from Switzerland). Bernard Joseph (of the Jewish Agency for Palestine) appealed to Sweden for assistance. Bernard contended that despite what Commander Becker of the War Shipping Board argued, cargo vessels could fairly easily be used to transport the children with very little alterations since the children could stay on the deck as long as they had blankets and a minimum of hygienic arrangements. As has been evidenced throughout this exhibit, there were a multitude of reasons invented as to why ships could not be utilized for these purposes: the German blockade in Swedish waters, & passenger ships were being used for international exchanges of prisoners of war. In addition, War Refugee Board representative (MJ Marks) shifted the responsibility to the Jewish Agency repeating that “this was not a War Refugee Board project.”58

In December 1944 and February 1945, the WRB received reports of the desperate situation of 8,000 children in France, who needed urgent care. The situation of non-French Jews was especially dire, since they were disqualified from French public relief.59 In February 1945, Florian Piskorski reported to Francis Switelik that “Poles are the biggest foreigners [sic] problem in France” and were divided into five groups. Unfortunately, this correspondence does not specify whether these refugees were Jewish. The first group was made up of 600,000 “last war-time immigrants” (of which 40 percent were children) and resided in Northern France. The next group were 9,000 “present war refugees” including 2,300 children living in Eastern and Southern France. Another group was made up of deportees who had worked under guard in farms in “rear operations zones”; this group included 5,000 children who were under 6 years old as well as 7,000 boys (7-15 years old) and 6,000 girls (7-15 years old). The French authorities were not taking action to address the problem. The letter requests financial assistance for “neglected youth in France” to attend universities, as well as for education for 13-17 year olds (1,500 boys and 500 girls) sixty percent of whom were deportees whose parents were in concentration camps or left in Poland. Forty percent of these youth were “old immigrants” but their education had been “neglected” for five years because of the war.60

58. WRB, Box 8, Folder 6, “Evacuation of Children From France to Palestine”: Florence Hodel, Memo for the Files, regarding phone conversation between Pehle and Lt. Commander Arthur Becker, November 1, 1944; MJ Marks to Mr. Joseph Friedman, Memo, November 3, 1944; Bernard Joseph of Jewish Agency for Palestine to Wollmar Bostrom of the Swedish Legation in D.C., December 13, 1944; Bernard Joseph to Joseph Friedman of the War Refugee Board in D.C., December 18, 1944; Matthew J. Marks (WRB representative), Memo for the Files, January 22, 1945.

59. Caffery to Secretary of State, original was from Joseph Schwartz to Moses Leavitt, Cable no. 819, December 6, 1944, WRB Box 10, Folder 18: France

60. Florence Hodel, Assistant Executive Director of WRB, to Mr. Francis Switelik, [note correct spelling should be Swietlik], President of the American Polish Relief Council, February 16, 1945, received originally from Florian Piskorski, February 14, 1945, WRB Box 10, Folder 18: France.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.